We're Still Pumping Water from Mines: The Path to Superintelligence

TBA

TBA

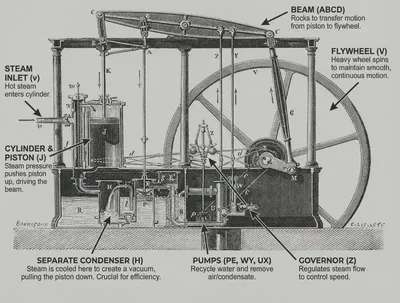

In 1769, James Watt unveiled his improved steam engine. It achieved 2 to 3 percent thermal efficiency—triple that of Thomas Newcomen’s earlier design. Engineers celebrated. Investors lined up. The future had arrived.

The celebration had been premature. By today’s standards, Watt’s gigantic machine was grotesquely wasteful, burning enormous quantities of coal to produce modest work. But it worked well enough for its time. These constraints limited applications to unique scenarios: pumping water from flooded mines where fuel was free and weight didn’t matter.

But what about the most celebrated application of steam engine, locomotives? Trevithick’s 1804 railway demonstration hauled ten tons of iron nine miles in four hours. It worked—with a excruciatingly slow speed. Then the locomotive was removed from service and converted back to a stationary engine. Because the rails couldn’t support its weight. For the next two decades, engineers debated whether locomotives should even exist or whether stationary engines with cable systems were safer. Commercial railways didn’t arrive until 1825, and didn’t transform society until decades after that.

Watt’s breakthrough wasn’t the answer—it was a stepping stone. More importantly, Watt himself had blocked the real breakthrough. He refused to build high-pressure engines, citing safety concerns. His patent prevented others from doing so. The innovations that made steam useful for transportation—Trevithick’s high-pressure designs—came only after Watt’s monopoly expired. Even then, the breakthrough technology sat unused for a generation because supporting infrastructure, materials science, and engineering practice needed time to catch up.

A century later, after relentless refinement, steam engines reached only 17 percent efficiency. By modern standards, still wasteful. For applications requiring power without bulk, steam had reached its theoretical ceiling. No amount of refinement would make a steam engine light enough for a practical automobile. Then internal combustion engines arrived. They didn’t improve on steam. They replaced it. Different fuel, different combustion principle, different constraints.

The Core Confusion

The point of retelling this history is because it repeats. We are living through this early history of industrial revolution with artificial intelligence.

Watt’s steam engine proved that mechanical power was possible through energy conversion. It took decades to discover what was actually a good source of energy and how to convert it into work. Early applications failed because the engine was too weak, too inefficient for anything where the cost of fuel and the weight of the mechanism is a concern. Engineers hadn’t yet understood the true power of the steam engine was not the steam: it was this idea of converting energy into work.

We face the same confusion with artificial intelligence. The success of LLMs seems to prove that machine intelligence is possible. We have seen LLMs reach high-level expertise in many areas, especially science, which is often deemed the peak of human intelligence. But we haven’t asked the critical question: what is the nature of these problems, and how are they related to our understanding of intelligence? The answer reveals a fundamental confusion.

The dominant narrative assumes intelligence equals knowledge. Build a system that knows more, and it becomes more intelligent. Scale up the parameters. Feed it more text. Add more reasoning tokens. Eventually, superintelligence emerges through sheer accumulation of effort.

This assumption shapes how we build AI. It is profoundly wrong. The LLM is the steam engine of our time.

Consider what our current systems excel at: answering questions about historical facts, explaining scientific concepts, generating text that sounds knowledgeable. They are magnificent encyclopedias that can converse. They know an astonishing amount about the world.

But consider what they catastrophically fail at: navigating a room without bumping into furniture. Learning from a single mistake. Adapting to an environment they weren’t explicitly trained on. Anything requiring sustained interaction with a changing reality.

These aren’t minor implementation details to be fixed with more training data. They point to a fundamental mismatch between the problem we’re solving (knowledge accumulation) and the problem intelligence actually evolved to solve.

What Intelligence Actually Does

What is intelligence then, if it is NOT about knowing things? Evolutionary biology seems to offer a clear answer: intelligence solves the problem of extracting value from limited experience with the environment.

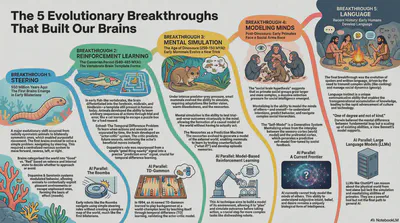

In his fascinating book, A Brief History of Intelligence, Max Solomon Bennett’s reveals how intelligence emerged not as knowledge accumulation but as increasingly sophisticated methods of processing environmental interaction:

Steering (~550 million years ago): Early bilaterians integrated internal states (hunger) with external stimuli (food) to navigate purposefully. This wasn’t about knowing the world—it was about converting sensation into directed action. The computational problem: how to move toward good things and away from bad things.

Reinforcing (~500 million years ago): Vertebrates evolved the basal ganglia, an actor-critic system using dopamine to solve the temporal credit assignment problem. They could learn which actions led to delayed rewards. The computational problem: how to extract causal patterns from sequential experience when outcomes are separated from actions by time.

Simulating (~100 million years ago): The mammalian neocortex enabled internal simulation—rendering reality mentally to test actions before performing them. This “world model” allowed vicarious trial and error, episodic memory, and counterfactual reasoning. The computational problem: how to maximize learning from limited real-world experience by creating cheap, fast internal experiences.

Mentalizing (~10-30 million years ago): Primates developed the prefrontal cortex, creating a simulation of other minds’ simulations. Theory of Mind, advanced imitation, anticipating future needs. The computational problem: how to learn from others’ experiences without directly experiencing them yourself.

Speaking (~100,000 years ago): Humans repurposed mentalizing areas for language through joint attention and proto-conversations. This enabled cumulative culture—ideas modified and improved across generations. The computational problem: how to transmit compressed representations of experience across individuals and time.

Notice the pattern: each breakthrough is about processing experience more efficiently, not storing more knowledge. A fish doesn’t know facts about water temperature or current—it learns from experience how to swim efficiently.

In a recent interview, Richard Sutton argues that our current generation of AI models have a fundamental flaw: they learn to predict what humans would say, not what actually happens in the world. He believes the fundamental principles of intelligence are shared across animals and that human-specific traits like language are just a “small veneer on the surface.” A squirrel doesn’t memorize encyclopedia entries about nuts—it learns from interaction where to find them, how to crack them, when to store them.

Does a squirrel have intelligence? Yes—absolutely. So does a cat, a dog, a crow solving a multi-step puzzle. This is intelligence without language: the ability to learn from limited experience, to adapt behavior based on environmental feedback, to generalize patterns to novel situations. This adaptive capacity is what intelligence fundamentally is.

Knowledge, by contrast, is a consequence of exercising this intelligence—our accumulated assumptions and understandings about the world (sometimes not even correct). Knowledge can be stored, transmitted, and compressed. But intelligence is the process that generates and applies knowledge through environmental interaction.

Geoffrey Hinton offers a different perspective, defining intelligence as the extreme convergence of global knowledge within limited weights. Because the internet’s trillions of data points cannot fit perfectly into finite parameters, the network is forced to find efficient coding methods, discovering deep, non-linear commonalities across disparate fields. In this view, language becomes a high-dimensional geometric problem where words are dynamic blocks that “handshake” with others—analogous to protein folding, where amino acid sequences spontaneously fold into the most stable, low-energy structure.

This is a profound insight about compression. The fact that the multitude of human languages can converge into stable weights suggests some universal structure to knowledge as represented through language. And yes—this compression is a form of intelligence. The ability to discover deep patterns across disparate domains, to find efficient representations, to generalize from vast data—this is genuine cognitive work.

But it’s not the complete picture of intelligence needed for superintelligence. Humans possess both types: the ability to compress and represent knowledge (pattern-finding) AND the ability to learn from experience and act adaptively (experiential learning). LLMs demonstrate that you can build impressive pattern-compression intelligence without experiential intelligence. A squirrel demonstrates that you can have rich experiential intelligence without vast compressed knowledge.

These are different computational problems that happen to coexist in humans. Current AI has mastered one; superintelligence requires both. The work we’ve done building pattern-compression systems isn’t wasted—it’s foundational. But it’s like building an exquisite steam engine: remarkable engineering that must be integrated into a fundamentally different architecture to achieve the next leap.

The Inversion: We Built It Backward

Current AI architectures represent a nearly perfect inversion of biological intelligence’s design principles.

Maximum knowledge, minimal experience. LLMs are trained on humanity’s accumulated text—Wikipedia articles, scientific papers, books, websites. Trillions of tokens of human knowledge compressed into model weights. But they receive zero training on sequential environmental interaction. They never experience navigating a space, manipulating objects, learning from the consequences of their actions, adapting to changing conditions.

It’s as if we raised a child by forcing them to memorize every book in the library while locked in a sensory deprivation chamber, never allowing them to touch anything, walk anywhere, or learn from a single mistake.

Andrej Karpathy calls this “summoning ghosts”—systems that eloquently discuss topics they’ve never experienced, imitating human data rather than learning through interaction.

The architectural manifestation of this inversion is striking. Karpathy diagnoses the core inefficiency: current models are over-distracted by memorization. They lack the modular separation between cognitive processing and knowledge storage. Everything is flattened into a single undifferentiated weight matrix—as if building a steam engine where the boiler, piston, and flywheel are merged into one undifferentiated mass of metal.

This matters because biological intelligence’s most important “limitation” is actually its core design feature: poor rote memory forces abstraction. Humans cannot memorize everything word-for-word, so we extract generalizable patterns. We forget specifics but remember principles. We compress experience into actionable heuristics rather than perfect recordings.

Interestingly, as we remember more, we become less creative—perfect recall crowds out the abstraction that drives innovation.

Current LLMs demonstrate this problem at scale. They drown in perfect recall. The KV cache (context window) acts as working memory, while the model weights represent a “hazy recollection” of pre-training—but both are fundamentally about retrieval, not processing. The system knows everything but learns nothing.

Karpathy’s idea of a “cognitive core” points toward the fix: an intelligent entity stripped of massive internet knowledge but containing the “magic” of problem-solving and strategy. He predicts this core could exist within just one billion parameters—a radical downsizing from current models—provided it’s trained on refined, high-quality experience rather than internet “slop.”

This echoes Bennett’s first evolutionary breakthrough: steering required remarkably little neural machinery to produce directed, purposeful behavior. A bilaterally symmetric organism doesn’t need to know facts about the ocean to navigate it effectively. It needs a tight experience-to-action loop.

We built systems that know about the world. We need systems that know how to act in the world. These are fundamentally different computational problems requiring fundamentally different architectures.

But Why Are LLMs So Capable?

If LLMs are solving the wrong problem—accumulating knowledge rather than learning from experience—why do they work so remarkably well? This paradox demands explanation. Systems built “backwards” still exhibit impressive reasoning, problem-solving, and adaptability within their training distribution. They ace advanced math competitions, write sophisticated code, engage in nuanced conversation. How?

The answer reveals something profound about human language itself: it encodes compressed experiential knowledge. When humans describe the world through language, we’re not just transmitting abstract symbols—we’re compressing centuries of collective experience into linguistic patterns.

Consider how we teach children. We don’t say “an object in motion stays in motion unless acted upon by an external force” as pure abstraction. We say “push the ball harder if you want it to roll further.” Language crystallizes experiential patterns into transmissible form. Recent research confirms this: LLMs trained on text achieve 97% accuracy at determining causal relationships between variable pairs across diverse domains like physics and biology, and they encode common sense and domain knowledge about causal mechanisms learned implicitly from linguistic patterns.

This explains LLM capabilities: they’re extracting the experiential residue embedded in human language. Every physics textbook, every how-to guide, every story about cause and effect—these compress actual experiences into words. By learning to predict these patterns at massive scale across trillions of tokens, LLMs reconstruct a shadowy simulacrum of experiential knowledge.

Moreover, knowledge accumulation at scale IS genuinely difficult and valuable. Minimizing prediction error across the entire distribution of human knowledge may be “the most difficult and general learning objective ever conceived”—one that forces models to learn grammar, logic, facts, common sense, and principles of countless domains simultaneously. This is real cognitive work, a genuine form of pattern-compression intelligence.

Successful attempts in test-time reasoning (OpenAI’s o1, DeepSeek R1) demonstrate that LLMs can spontaneously develop reasoning strategies when trained against verifiable rewards. The result? DeepSeek R1’s verbose reasoning output reads remarkably like deliberative thought. I have detailed my experience here.

But this kind of effort has a limit. Think about the famous thought experiment: Mary, a brilliant color scientist who knows everything physical about color: every wavelength, every neural pathway, every physical law governing light perception. But Mary has lived her entire life in a black-and-white room. When she finally steps outside and sees red for the first time, does she learn something new?

This is precisely the situation with LLMs. They possess encyclopedic knowledge about the world—every physics principle, every causal relationship humans have documented, every pattern extracted from trillions of tokens. But like Mary, their understanding remains derived from descriptions rather than experience. LLMs are vulnerable to “fluent fallacies”—answers that are linguistically plausible but physically nonsensical. They can eloquently discuss concepts they’ve never experienced, generating textbook-style explanations through pattern matching that mimics deep understanding without possessing it.

The embodied cognition research makes this concrete: because LLMs train solely on text, their semantic representations lack grounding in sensorimotor experience. Consider trying to teach someone to ride a bicycle using only written instructions—someone who has never seen a bicycle, never felt motion, never experienced balance. You can write perfectly accurate descriptions: “Lean slightly into turns,” “Maintain forward momentum,” “Balance through subtle weight shifts.” But the student, having memorized every manual, still doesn’t know what balance feels like. They lack the kinesthetic sense—the embodied knowledge that comes from falling off and catching yourself, from feeling the bike wobble and learning to correct it.

This is precisely LLMs’ situation with pain perception, emotional responses, or physical manipulation. They possess accurate linguistic descriptions but cannot access the phenomenal substrate those descriptions reference. Language can point toward these experiences, but it cannot simulate them—revealing the fundamental difference between linguistic representation and experiential reality.

If you have tried to discuss movies with AI, you will know what I mean. An AI can pull film reviews and give you an eloquent lecture. But it has never actually watched it.

So knowledge IS important—just not sufficient. LLMs demonstrate you can build impressive pattern-compression intelligence by extracting experiential residue from human language. But this is like learning about swimming by reading every book ever written about swimming. You’ll know the physics of buoyancy, the history of swimming techniques, the biomechanics of efficient strokes. You might even offer helpful coaching tips. But throw you in deep water, and you’ll drown.

The compressed experiential knowledge in human language provides a foundation—a remarkable starting point. But superintelligence requires both: the knowledge extracted from human civilization AND the ability to generate new experiential knowledge through environmental interaction. LLMs solved half the puzzle brilliantly. Now we need the other half.

Transformers are Great, Until They are not

The world generates experience faster than any system can memorize responses. Consider a robot learning to manipulate objects. The combinatorial space of possible object configurations, hand positions, force applications, and environmental variations is effectively infinite. No amount of pre-training on text descriptions of manipulation can cover this space.

Biological systems solve this through experiential learning: a baby doesn’t memorize “when object X is at angle Y, apply force Z.” Instead, it learns general principles of object manipulation through interaction—developing intuitions about weight, friction, balance, momentum. These principles generalize to novel situations precisely because they weren’t memorized but abstracted from limited experience.

Current transformers, as implemented, struggle with this. They are stateless: each interaction is independent. There is no native mechanism for “this interaction updated my model.” They can memorize “what happened” but lack efficient ways to update “how to act.”

This doesn’t mean transformers are dead ends. The architecture is a remarkable starting point—flexible enough to accommodate structural innovations. We’ve already seen promising augmentations: DeepSeek’s 2025 breakthroughs in mixture-of-experts scaling, improvements in efficient attention mechanisms, architectural additions for better memory. Over the next few years, more innovations will likely be integrated, significantly increasing efficiency and performance.

But current approaches to experience-learning are fundamentally mismatched. Consider reinforcement learning and the entire alignment effort. For anyone who sees what happens under the hood, it’s an engineering marvel that RLHF works at all. Karpathy has a pithy phrase for this: “sucking supervision through a straw.” Giving a single reward at the end of a long task forces the model to guess which specific actions led to success. This approach—bolting experience-processing onto an architecture designed for knowledge retrieval—is working against the grain.

More critically, models lack the mechanisms biological intelligence uses: no consolidation process analogous to sleep, where experiences are reconciled with existing knowledge; no temporal difference learning vertebrates evolved 500 million years ago to propagate credit backward through action sequences; no tight perception-action loops that enable real-time adaptation.

These aren’t mere implementation details. They represent a fundamental mismatch between the computational problem transformers were designed to solve (parallel processing of static text) and the problem experience-based learning requires (sequential interaction with dynamic environments).

To be clear: the transformer is a landmark achievement. That such a simple idea yields such remarkable results is beyond anyone’s wildest dream. If we were content with what ChatGPT can do now—which is already far more than the steam engine accomplished for the Victorians—we could settle with the transformer architecture.

But we are more ambitious. We want to use the steam engine in automobiles and airplanes, where efficiency and weight become critical constraints. This demands significant architectural revision, not incremental refinement.

If we are to build superintelligence, it will require adaptive behavior in novel situations. Adaptation demands learning from interaction, not just retrieval from memory. A system that can only retrieve cannot adapt to situations beyond its training distribution. It can appear intelligent within the bounds of what it has memorized, but it lacks the capacity to learn new behaviors from experience.

The path forward isn’t simply abandoning transformers—it’s recognizing what they excel at (pattern-compression intelligence) and what they’re fundamentally mismatched for (experience-based learning). Just as steam engine principles weren’t discarded but adapted and integrated into new contexts, transformer architectures may evolve and find their place. But the missing piece—the experiential learning component—requires architectural innovations that address the core computational problem intelligence evolved to solve.

The Bitter Lesson, Reimagined

The steam engine emerged from a simple observation: a boiling kettle pushes its lid—this power can be harnessed. From this simple observation of physics to Watt’s working engine required tremendous engineering. But that effort seems straightforward compared to building advanced machine intelligence.

When the term artificial intelligence was first coined at Dartmouth in the 1950s, we were at the height of human engineering endeavors. Like Cyrus Smith in Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island, who transformed a barren volcanic rock into a thriving colony—producing fire from nothing, forging iron, manufacturing nitroglycerin, even building a seaworthy ship—engineers believed they possessed the knowledge to construct anything, including intelligence itself.

Building machine intelligence proved to be a much harder task. What the Dartmouth participants thought they could figure out in a few months took more than 70 years to get to what we have now. And we are nowhere close to cracking the real problem.

What is the challenge of building artificial intelligence? It is the choice of path: what to build, and what NOT to build. The triumph of the current wave of AI rests on a profound insight: to build better AI, we need to remove human from it.

This is what is known as “The Bitter Lesson.” Richard Sutton’s analysis of 70 years of AI research reveals a pattern: general methods leveraging computation ultimately outperform approaches based on human knowledge. Hand-crafted chess strategies couldn’t beat AlphaZero’s autonomous learning. Hand-crafted image features couldn’t beat neural networks trained on billions of images.

This lesson enabled the LLM revolution: don’t encode grammar rules—just scale the model and data. Let transformers discover patterns through compression. Trust computation over human insight.

For the last three years, the scaling law worked miracles. But we are already reaching a plateau. LLMs may squeeze some single-digit performance gains, but if true intelligence is our goal, this setup falls short—just like steam engines two hundred years ago.

For Sutton, there are three architectural limitations to our current AI tech. First, LLMs lack world models—they predict what humans say about situations, not what the world actually does. They say “don’t touch the kettle, it’s hot” from pattern matching, not understanding causality. Second, they have no ground truth. Unlike agents with clear scores, LLMs have no objective standard for correctness. Without verifiable feedback, they cannot truly learn. Third, they cannot learn from experience. LLMs are static after training. They don’t experience “surprise” or update when reality contradicts predictions.

Sutton argues intelligence is the computational part of the ability to achieve goals. Predicting tokens is passive calculation, not environmental action. To understand AGI, we must understand the squirrel: it learns through continuous perception, action, and reward without human-labeled data. Language is merely decoration on the deep, experiential intelligence humans share with animals.

True AGI requires many components: a policy that maps current state to best action; a value function that assesses long-term outcomes across extended reward cycles; perception that converts sensory input to useful representations; and a world transition model that understands causality—how the world changes when you act. Notice what’s missing: massive knowledge databases. These components process experience, not retrieve information.

In 2024, Sutton and David Silver published “Welcome to the Era of Experience,” proposing AI has passed through three eras. The Era of Simulation, exemplified by AlphaGo, where agents learn from millions of self-generated games in simulated environments. The Era of Human Data, exemplified by GPT-3, where models train on humanity’s accumulated text and images. And now the Era of Experience, beginning with AlphaProof in 2024, where agents achieve superhuman capabilities through direct environmental interaction.

Experience is “data you get when you interact with the world”—sequential, causal, responsive. Your actions change state. Outcomes depend on decisions. This fundamentally differs from reading about the world. The Era of Human Data was a detour proving neural networks could scale. But it trained on the wrong data: human descriptions of reality rather than reality itself.

Sutton’s bitter lesson can now be reimagined under this new development: general methods learning from raw experience will outperform methods using human-distilled knowledge, however efficiently compressed. LLMs are a “local optimum”—revolutionary enough to seem like the answer, but solving the wrong problem. The new bitter lesson: experience beats accumulated human data.

The Rise of World Models

Experience is nice, you say. But how?

There is currently no clear consensus on which technology can implement experience-based learning at scale. Knowledge is low-hanging fruit because it’s relatively easy to crawl the internet and compile digital texts for LLMs to train on. But what is the format of experience? How do we ingest experience? What kind of agency can we give to AI to form effective perception-action loops?

The answer is taking shape across multiple fronts, and it looks nothing like text corpora.

The format of experience turns out to be continuous streams of sensing and acting. In November 2025, researchers released GEN-0, an embodied foundation model pretrained on 270,000 hours of real robot manipulation data—not curated demonstrations, but raw continuous streams captured at human-level reflex speeds. A single data session contains diverse atomic skills unfolding naturally: grasping, inserting, twisting, opening, bimanual coordination. The system learns from 10,000 new hours every week.

This is radically different from text training. Experience data is sequential and causal—your actions change state, outcomes depend on decisions, the world pushes back. A robot learning to grasp a bottle doesn’t receive a paragraph describing “proper grasping technique.” It receives continuous sensory feedback: visual input of the bottle’s position, tactile signals of grip pressure, proprioceptive awareness of arm position, and the immediate consequence—success or failure. This perception-action loop, iterated thousands of times, is what creates experiential knowledge.

World models represent the most prominent architectural approach: systems that learn internal simulations of their environment to predict outcomes and plan actions. Think of them as artificial versions of Bennett’s third evolutionary breakthrough—simulation—where mammals internalized reality to enable vicarious trial and error.

At the February 2025 AI Action Summit in Paris, Yann LeCun argued that world models are better suited for “human-level intelligence” than LLMs because language models fundamentally lack reasoning capabilities about the physical world. In December 2025, he put billions behind this conviction, launching AMI Labs, a startup focused entirely on world model AI.

LeCun’s vision, formalized in his 2022 paper “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence,” describes systems that build internal models of physics and causality, maintain persistent memory across interactions, simulate “what if” scenarios before acting, and plan complex action sequences toward goals.

The technical implementations are accelerating. Google’s Genie 3 (August 2025) generates playable 3D environments in real-time at 24 FPS from text descriptions—interactive worlds with consistent physics that respond to your actions. OpenAI’s Sora 2 demonstrates emergent 3D consistency, object permanence, and basic physics understanding. The company explicitly positions it as building “capable simulators of the physical and digital world,” with the ability to simulate actions affecting world state: painter strokes persisting on canvas, bite marks appearing on food.

DeepMind’s DreamerV3 uses Recurrent State-Space Models to learn compact representations of environment dynamics, then “dreams” future scenarios to plan actions—achieving breakthrough performance across Atari games, robotic manipulation, and continuous control tasks. The system learns to predict future states and rewards in a learned representation space rather than trying to reconstruct every pixel. This is crucial: you don’t need photorealistic simulation, just sufficient abstraction to plan effectively.

But world models aren’t the only path. Meta’s V-JEPA 2 takes a different approach: self-supervised learning from video. Pretrained on over 1 million hours of internet video, it learns to predict masked spatiotemporal regions—essentially learning physics and object dynamics from watching the world unfold. Remarkably, after training on just 62 hours of unlabeled robot videos, V-JEPA 2 achieved zero-shot deployment on robotic arms for pick-and-place tasks. The system learned what objects are—how they behave, how weight distributes, how transparent materials interact with light—without explicit instruction.

Robotics foundation models represent yet another direction. Systems like RT-2 reconceptualize robot actions as tokens in a symbolic language, enabling transfer from internet-scale vision-language data to physical manipulation. PaLM-E injects continuous sensory inputs—images, low-level states, 3D scene representations—directly into language embedding space, creating multimodal models that ground language in physical experience.

The market believes this is real. PitchBook projects world models in gaming alone growing from $1.2B (2022-2025) to $276B by 2030. In January 2025, Nvidia launched Cosmos, a World Foundation Model Platform specifically for Physical AI in robotics and autonomous vehicles. Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs released their “Marble” platform. The infrastructure is forming.

What unites these approaches is the core insight: experience isn’t descriptions of the world—it’s interaction with the world. Not text explaining object permanence, but systems that discover object permanence through observation. Not manuals about grasping, but continuous sensorimotor streams where actions have consequences and the world teaches through feedback.

This directly echoes the bitter lesson reimagined: general methods learning from raw experience will outperform methods using human-distilled knowledge, however efficiently compressed. LLMs proved that pattern-compression intelligence can reach remarkable heights. World models and embodied AI are proving that experiential intelligence requires fundamentally different architectures—ones that learn through doing, not just reading about doing.

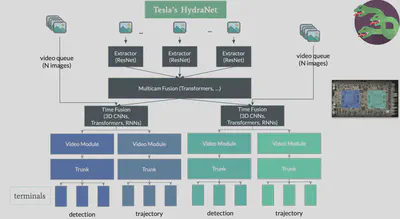

Tesla’s Full Self-Driving represents this principle at massive scale in the real world. The system learns driving behavior from over 1.6 billion miles of real-world driving data—continuous streams of camera input paired with human driving decisions. This is pure experiential learning: what you see (eight cameras, 360-degree vision) → what you do (steering angle, acceleration, braking) → what happens (successful navigation or correction needed).

Early autonomous driving systems relied on hand-coded rules: “if pedestrian detected within X meters, apply Y braking force.” These rule-based approaches proved brittle—they failed in edge cases engineers hadn’t anticipated. Tesla’s end-to-end neural network approach instead learns the mapping from visual input to driving actions directly from experience. The system discovers what matters: a plastic bag blowing across the road behaves differently from a child running; a car with its turn signal on may or may not actually turn; rain changes how headlights reflect.

This is driving intelligence—the ability to act based on what you perceive—not knowledge expressed in words. You cannot write a manual comprehensive enough to cover every possible driving scenario. But you can learn from millions of miles of humans successfully navigating those scenarios, extracting the implicit patterns that make someone a good driver. FSD doesn’t “know about” driving in the way an LLM knows about it from reading traffic laws and driving instruction texts. It knows how to drive from having processed billions of examples of perception-action-outcome sequences in real environments.

The Path Forward

Picture a robot on Mars in 2035. The communication delay from Earth is twenty-two minutes. Mission Control cannot provide real-time guidance. The robot encounters a geological formation unlike anything in its training data—a crystalline structure protruding from regolith that could be scientifically invaluable or structurally fragile.

On Earth, engineers programmed rules for hundreds of rock types, soil densities, temperature ranges. But Mars doesn’t care about Earth rules. The gravity is different. The atmospheric pressure is different. The minerals form in ways Earth chemistry never produced. The robot cannot search a database of “how to handle Martian crystalline formations” because no such database exists.

Instead, its world model runs internal simulations: What happens if I apply pressure here? The structure might fracture—simulate that. What if I approach from this angle? The regolith might shift—simulate that. What if I use the brush first to clear debris? The robot tests dozens of approaches in its learned representation of physics, evaluating outcomes before touching anything.

Then it acts. Not because it memorized this scenario on Earth, but because it learned from millions of interactions what materials are—how forces propagate through structures, how different substances respond to pressure, how to update predictions when reality surprises you.

When the first sample crumbles unexpectedly, the robot doesn’t fail catastrophically. It updates its internal model: This material is more brittle than predicted. Adjust approach. It learns from the mistake in real-time, trying a gentler method. The second attempt succeeds.

That robot knows something no Earth-trained system could know: what Martian regolith feels like under different conditions. Not from reading geology papers, but from interacting with an alien world and updating its understanding based on what actually happens. This is experiential intelligence—the ability to learn from environments you’ve never encountered, to adapt when your predictions fail, to extract patterns from raw interaction with reality.

The steam engine worked for pumping water from mines. We’re still in the mines. The question isn’t when we’ll build superintelligence. It’s whether we’ll recognize that the path forward runs through experience, not just scale.

Sources

Historical Context: Steam Engines

- Watt steam engine - Wikipedia

- Watt Steam Engine - World History Encyclopedia

- Smeaton Vs Watt: The Steam Engine Rivalry - Institution of Civil Engineers

- Thomas Newcomen and the Steam Engine - Engineering and Technology History Wiki

Evolutionary Intelligence

- Bennett, Max Solomon. A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our Brains. HarperCollins, 2023. Publisher site

- The Five Breakthroughs of Intelligence — Book review of Max Bennett’s A Brief History of Intelligence

Richard Sutton: The Bitter Lesson and Era of Experience

- Sutton, Richard. “The Bitter Lesson” (2019)

- Silver, David and Richard S. Sutton. “Welcome to the Era of Experience” (2024)

- Is ‘The Era of Experience’ Upon Us? Researchers Propose AI Agents Learn From the World

- Bitter lesson - Wikipedia

Andrej Karpathy: Cognitive Core and “Summoning Ghosts”

- Karpathy, Andrej. “2025 LLM Year in Review” (January 2026)

- AI Guru Andrej Karpathy Unveils 2025 Annual Summary: LLMs Step into New Era of “Ghost Intelligence”

- Andrej Karpathy — “We’re summoning ghosts, not building animals” (Dwarkesh Patel interview)

Geoffrey Hinton: Compression, Intelligence, and Timeline Predictions

- Geoffrey Hinton – Facts – 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics

- Geoffrey Hinton on AI intelligence and superintelligence

- AI Pioneer Geoffrey Hinton Warns of Superintelligence Within Decades

Yann LeCun: World Models and AMI Labs

- LeCun, Yann. “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence” (Version 0.9.2, 2022)

- Yann LeCun confirms his new ‘world model’ startup, reportedly seeks $5B+ valuation (December 2025)

- Yann LeCun Launches Advanced Machine Intelligence With Alex LeBrun as CEO

- Yann LeCun: “We are not going to get to human-level AI just by scaling LLMs” Korea IT Times (Paris AI Summit, February 2025)

World Labs and Other World Model Startups

- Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs emerges from stealth with $230M in funding TechCrunch

- World Labs launches Marble platform for spatial intelligence The Verge

DeepMind Research: World Models and Reinforcement Learning

- Hafner, Danijar, et al. “Mastering diverse control tasks through world models” Nature 640 (2025): 647-653

- Introducing Dreamer: Scalable Reinforcement Learning Using World Models

- Mastering Diverse Domains through World Models (DreamerV3)

Meta Research: V-JEPA and Visual Prediction

- Introducing the V-JEPA 2 world model and new benchmarks for physical reasoning

- V-JEPA 2: Self-Supervised Video Models Enable Understanding, Prediction and Planning

- Meta’s V-JEPA 2: Advancing World Models and Physical Reasoning in AI

NVIDIA Cosmos: Physical AI Platform

- NVIDIA Launches Cosmos World Foundation Model Platform to Accelerate Physical AI Development (January 2025)

- NVIDIA Cosmos: World Foundation Models Powering Physical AI

- CES 2025: NVIDIA launches Cosmos world foundation model, expands Omniverse

DeepSeek: Mixture-of-Experts and Reasoning Breakthroughs

- DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning (January 2025)

- DeepSeek’s reasoning AI shows power of small models, efficiently trained

- A Technical Tour of the DeepSeek Models from V3 to V3.2

- DeepSeek-R1 incentivizes reasoning in LLMs through reinforcement learning Nature (2025)

LLM Capabilities: Causal Reasoning and Knowledge

- The State Of LLMs 2025: Progress, Progress, and Predictions

- Unveiling Causal Reasoning in Large Language Models: Reality or Mirage? (NeurIPS 2024)

- Commonsense reasoning in AI systems

- Inducing Causal World Models in LLMs for Zero-Shot Physical Reasoning (2025)

- Can Large Language Models Infer Causal Relationships from Real-World Text?

- LLMs could serve as world models for training AI agents

Embodied Cognition and Symbol Grounding

- Symbol ungrounding: what the successes (and failures) of large language models reveal about human cognition (2024)

- Will Multimodal Large Language Models Ever Achieve Deep Understanding of the World? Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience (2025)

World Models: Technical Implementations and Market Landscape

- World Models Are the Next Big Thing In AI. Here’s Why. Built In (2025)

- World Models Reading List: The Papers You Actually Need in 2025

- ‘World Models,’ an Old Idea in AI, Mount a Comeback Quanta Magazine

- From ‘AI slop’ to world models: What to expect from AI in 2026 Euronews

- What’s next for AI in 2026 MIT Technology Review (includes market projections)

Embodied Foundation Models and Robotics AI

- GEN-0: Embodied Foundation Models That Scale with Physical Interaction Generalist AI (November 2025)

- Foundation models in robotics: Applications, challenges, and the future SAGE Journals

- What foundation models can bring for robot learning in manipulation: A survey SAGE Journals

- Embodied AI and Data Generation for Robotics NIST

- Brohan, Anthony, et al. “RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control” DeepMind (2023)

- Driess, Danny, et al. “PaLM-E: An Embodied Multimodal Language Model” arXiv (2023)

Google Genie and OpenAI Sora

- Video generation models as world simulators OpenAI

- Sora 2 is here OpenAI

- OpenAI’s Sora 2: Redefining Safe, Physics-Driven Video AI AI Magazine

Tesla Full Self-Driving: End-to-End Experiential Learning

- Tesla AI Day 2022: Full Self-Driving Tesla (August 2022)

- Tesla’s Approach to Autonomy Tesla AI

- Hu, Anthony, et al. “Model-Based Imitation Learning for Urban Driving” NeurIPS 2022

- How Tesla’s Neural Network Learns to Drive Not Boring

- Understanding Tesla’s Autopilot and Full Self-Driving The Verge